ZUP v Nash Manufacturing

ZUP, LLC v. Nash Manufacturing, Inc.

No. 2017-1601 Fed. Cir. July 25, 2018

Opinion by Chief Judge Prost with Circuit Judge Lourie.

Dissenting opinion filed by Circuit Judge Newman.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“Federal Circuit”) affirmed the decision of the district court invalidating claims of U.S. Patent No. 8,292,681 (“the ’681 patent”) as obvious. The issues on appeal pertained to (1) motivation to combine the prior art references in the way claimed in the ’681 patent, and (2) the district court’s evaluation of evidence of secondary considerations.

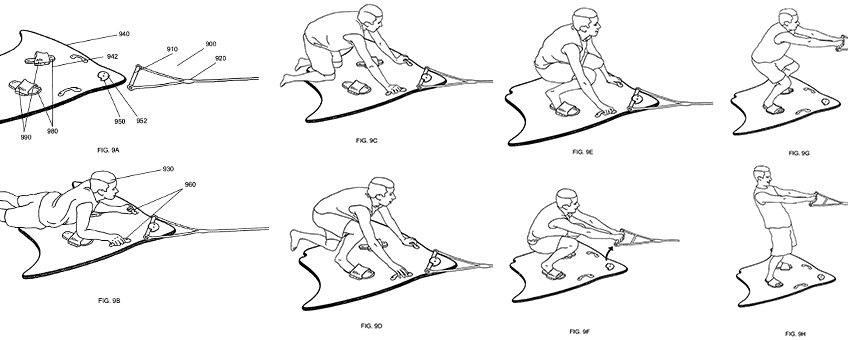

The claims of the ’681 patent cover a water recreational board and a method of riding the board. A rider simultaneously uses side-by-side handles and side-byside foot bindings to help maneuver between various riding positions. The board assists riders who have difficulty pulling themselves into a standing position while being towed behind a motorboat.

Chief Judge Prost, writing for the majority, stated that because of “significant evidence presented by Nash regarding the consistent desire for riders to change positions while riding water recreational boards (and the need to maintain stability while doing so), and given that the elements of the ’681 patent were used in the prior art for this very purpose, there is no genuine dispute as to the existence of a motivation to combine.”

Nash introduced no evidence concerning secondary considerations, while ZUP submitted two affidavits demonstrating secondary considerations. The Court acknowledged that the burden of persuasion was on the challenger (Nash), but stated that “a patentee bears the burden of production with respect to evidence of secondary considerations of non-obviousness.” As a result, it was not necessary for Nash to present evidence of secondary considerations to obtain summary judgment. The Court noted that obviousness is “a legal determination, and a strong showing of obviousness may stand even in the face of considerable evidence of secondary considerations.”

The Court noted that obviousness is “a legal determination, and a strong showing of obviousness may stand even in the face of considerable evidence of secondary considerations.”

In an attempt to show long-felt but unresolved need, ZUP proffered expert testimony stating that the water sports market had long focused on creating stability for a rider and that “it was a general frustration to the industry that there was no product that would enable the weakest and most athletically challenged members of the boating community to ski or wakeboard.” Further, Nash’s president, during negotiations stated “You have a great product by the way!” and that ZUP was “spot on” with its product. The Court dismissed the argument, finding that since differences between the prior art and the claimed invention were minimal, no long-felt need was solved.

Nash had obtained a sample product from ZUP during the parties’ initial business discussions. The Court rejected ZUP’s position that Nash copied the product, stating that for the Nash board “to resemble the claimed invention, a user would need to ignore Nash’s instructions on how to use the (Nash) Versa Board — instructions that specifically discourage users from keeping the handles attached to the board while standing.”

Judge Newman dissented, stating that the majority reached its conclusion based “on incorrect application of the law of obviousness and without regard to the principles of summary judgment.” Judge Newman stated that all agreed that the ZUP invention was novel, but that “the district court and my colleagues hold that because some prior art wakeboards have handles and some have foot supports, nothing more is needed for summary judgment of obviousness.”

In the dissent’s view, the majority deemed “that only three of the four Graham factors are considered in order to establish a prima facie case of obviousness, and that the fourth Graham factor is applied only in rebuttal, whereby the fourth factor must be of sufficient weight to outweigh and thereby rebut the first three factors.” Judge Newnan stated that the fourth Graham factor, objective indicia of secondary considerations, “must be considered together with the other evidence, and not separated out and required to outweigh or rebut the other factors.” She went on to note the importance of objective indicia in overcoming hindsight, noting that neither the lower court nor the majority identified any suggestion in the prior art to make the modifications presented by the claimed invention, stating that “the only source of these modifications is judicial hindsight.”

The dissent also posited that the district court misapplied the factor of long-felt need. “Motivation to solve a known problem is not motivation to make a specific solution.” “(The inventor’s) realignment of known elements in a crowded field, achieving benefits not previously achieved, weighs against obviousness.”

With regard to copying, Nash possessed the ZUP product prior to producing its product. The majority indicated that because ZUP did not give Nash a “blueprint,” evidence of copying is diminished. However, Judge Newman replied that “[n]o precedent, no logic, requires a ‘blueprint’ in order to copy a simple structure in plain view and possessed by the accused infringer.”

Read more: Federal Bar member attorneys may access the full case summary by registered patent attorney B.C. “Bill” Killough in the August 2018 issue of Federal Circuit Case Digest.

B.C. Killough is a registered patent attorney based in Charleston, SC. On behalf of his clients, Bill has obtained more than 300 United States patents, participated in prosecuting more than 100 foreign patent applications and he has filed more than 1000 trademark applications with the US Patent and Trademark Offices.

B.C. Killough is a registered patent attorney based in Charleston, SC. On behalf of his clients, Bill has obtained more than 300 United States patents, participated in prosecuting more than 100 foreign patent applications and he has filed more than 1000 trademark applications with the US Patent and Trademark Offices.

Additionally, you may read the full opinion here.