Travel Sentry v David Tropp

TRAVEL SENTRY, INC., Plaintiff-Cross-Appellant v. DAVID A. TROPP, Defendant-Appellant

2016-2386, 2016-2387, 2016-2714, 2017-1025 Appeals from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York in Nos. 1:06-cv-06415-ENV- RLM, 1:08-cv-04446-ENV-RLM, Judge Eric N. Vitaliano.

For the third time, the Court presided over this dispute regarding whether Travel Sentry, Inc. (“Travel Sentry”) and its licensees infringed one or more claims of two patents issued to appellant David A. Tropp (“Tropp”). In this iteration, the Court reversed the district court’s entry of summary judgment that Travel Sentry and its licensees did not directly infringe any of the method claims recited in the patents under 35 U.S.C. § 271(a).

This case closely tracked the developments of, and presented similar issues to, another well-traveled case, Akamai Technologies, Inc. v. Limelight Networks, Inc., which the Court discussed at length in this opinion. Akamai examined the respective scopes of divided and induced infringement.

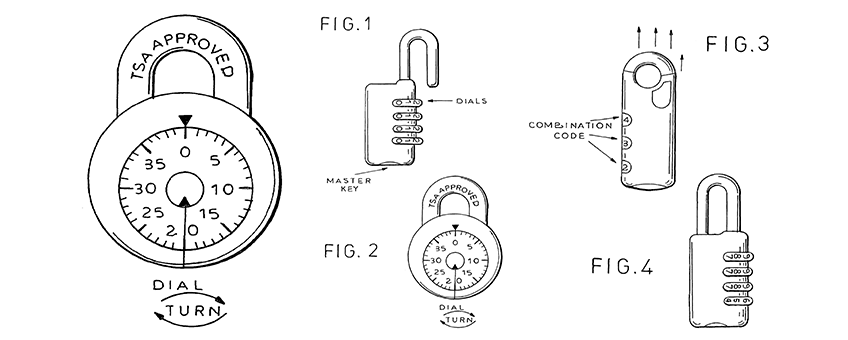

Tropp, through his company, administers a lock system that permits the Transportation Security Administration (“TSA”) to unlock, inspect, and relock checked baggage. Travel Sentry also administers a system that enables a traveler to lock a checked bag, while allowing TSA to open the lock, search the bag, and relock it. Travel Sentry entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with TSA. The MOU states that Travel Sentry will supply TSA with master keys (termed “passkeys”) to open checked baggage secured with certified locks.

The Court noted that the Supreme Court in Akamai reaffirmed the principle that, “where there has been no direct infringement, there can be no inducement of infringement under § 271(b).” On remand of Akamai (Akamai V), the Federal Circuit determined that “[w]here more than one actor is involved in practicing the steps, a court must determine whether the acts of one are attributable to the other such that a single entity is responsible for the infringement” and that an entity will be held “responsible for others’ performance of method steps [under § 271(a)] in two sets of circumstances: (1) where that entity directs or controls others’ performance, and (2) where the actors form a joint enterprise.”

Under Akamai V liability exists under§271(a) when an alleged infringer 1) conditions participation in an activity or receipt of a benefit upon performance of a step or steps of a patented method; and 2) establishes the manner or timing of that performance. The Federal Circuit discussed the application of the Akamai two prong test in the recent case, Eli Lilly v. Teva Parenteral Medicines, 845 F.3d 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The Court noted that Akamai V and Eli Lilly highlight the importance of correctly identifying the relevant “activity” or “benefit” that is being conditioned upon the performance of one or more claim steps. The cases also emphasize that the context of the claims and conduct in a particular case will inform whether attribution is proper under Akamai V’s two-prong test.”

The district court reasoned that summary judgment was appropriate because “there is simply no evidence that Travel Sentry had any influence whatsoever on the third and fourth steps of the [patented] method carried out by the TSA, let alone ‘masterminded’ the entire patented process.” The Court stated that the district court committed three specific errors. It misidentified the relevant “activity” at issue; it misapprehended the types of “benefits” that can satisfy Akamai V’s first prong; finally, it mischaracterized what is required for one to “condition” a third party’s participation in an activity or receipt of a benefit on the third party’s performance of one or more claim steps.

The district court did not explain why the relevant activity in this case is “luggage screening.” The Court found that the MOU describes “a far more specific set of objectives.” The TSA agreed to make good faith efforts to “distribute the passkeys and information provided by Travel Sentry on the use of the passkeys,” to “use the passkeys to open checked baggage secured with Travel Sentry certified locks whenever practicable,” and to have its employees “relock Travel Sentry locks after bags are inspected.” The “activity” is screening luggage that TSA knows can be opened with the passkeys provided by Travel Sentry.

The district court reasoned that TSA “screens luggage because of the screening mandate of Congress, not because of any purported intangible benefits.” The Court stated that the district court’s mischaracterization of the relevant activity tainted its view of the “benefits” Travel Sentry conditioned on TSA’s performance. “A reasonable juror could conclude that the ‘benefit’ to TSA contemplated in the MOU is the ability to open identifiable luggage using a master key, which would obviate the need to break open the lock. Indeed, it is irrelevant that TSA screens luggage pursuant a mandate from Congress—what matters is how the agency accomplishes its luggage screening objective, and whether a benefit flows to TSA from the particular screening method it has chosen.” The Court noted that the benefit could be tangible or intangible, such as “promotion of the public’s perception of the agency.”

The third step of the method claim requires having an identification structure that signals to a luggage screener that the lock may be opened with a master key. The fourth step requires having the luggage screener, acting pursuant to the agreement, look for the identification structure, and use the master key to open the lock. These steps define the relevant activity. According to the Court, the benefits flowing to TSA can only be realized if TSA performs the final two claim steps.

With regard to the second prong of Akamai V, the Court concluded that a reasonable jury could find that Travel Sentry has established the manner or timing of TSA’s performance. Travel Sentry does not require TSA to accomplish “a series of technological feats in order to participate in the Travel Sentry standard” or supervise “TSA’s conduct or has employees or other resources dedicated to resolve issues TSA encounters along the way. But the record suggests that, in order for TSA to receive the benefits that flow from inspecting luggage with Travel Sentry’s dual-access locks, it must use the passkeys that Travel Sentry distributed—and, on request, replaces—to open those locks, pursuant to the MOU. Travel Sentry has also provided TSA with training materials to help TSA screeners identify luggage bearing such locks. A reasonable jury could conclude that those activities by Travel Sentry do establish the manner of TSA’s performance of the final two claim steps.”

The Court also noted that in copyright law that “an actor ‘infringes vicariously by profiting from direct infringement’ if that actor has the right and ability to stop or limit the infringement.” See Akamai V (citing Metro–Goldwyn–Mayer Studios Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913, 930 (2005)). “Travel Sentry ‘has the right and ability to stop or limit’ TSA’s ability to practice the final two claim steps—and thus receive the benefits that follow from practicing those steps—through a number of means.”

Read more: Federal Bar member attorneys may access the full case summary by registered patent attorney B.C. “Bill” Killough in the January 2018 issue of Federal Circuit Case Digest.

B.C. Killough is a registered patent attorney based in Charleston, SC. On behalf of his clients, Bill has obtained more than 300 United States patents, participated in prosecuting more than 100 foreign patent applications and he has filed more than 1000 trademark applications with the US Patent and Trademark Offices.

B.C. Killough is a registered patent attorney based in Charleston, SC. On behalf of his clients, Bill has obtained more than 300 United States patents, participated in prosecuting more than 100 foreign patent applications and he has filed more than 1000 trademark applications with the US Patent and Trademark Offices.

Additionally, you may read the full opinion here.